I've spent a couple of months reading all sorts of articles and news about Free Software, Open-Source, licensing and more importantly the different business model strategies you can adopt to support financially your next amazing Free Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) project.

I want to summarize in this series of articles the most important things that I've learnt and that I think everyone in the industry should know.

These articles are beginner-friendly. You do not need any background in software licensing, or even in software development to read it. In fact, my wife who is not in technology in any ways, was able to comprehend its content.

I'll start by a few definitions. If you are in tech, while it may appear trivial I encourage you NOT to skip that section, especially if you consider yourself as a junior/mid-level developer, but it also applies to many senior developers. I've read many mischaracterizations and misunderstandings on the very meaning of Free Software, Open Source and the different licenses to know that you might be confused about these notions maybe without realizing it. As a matter of fact, lots of tech/business articles happily make these confusions everyday.

Free Software

Free Software is a term invented by Richard Stallman. It was invented at a time when almost every piece of software was proprietary. No one was ever sharing source code. The software industry was following the same principle as the other industries: you make a product inside your company, you sell it and you keep your recipe ultra secret. A business model based on selling ultra-expensive perpetual licenses. Free Software's motto is "Free as in Freedom". Freedom for the user as opposed to the developers. It all started when Richard got frustrated after his printer couldn't work and he realized he didn't have access to its source code to fix it. And everyone was refusing giving him the source code because they had signed a NDA. You can read the whole story on gnu.org.

What are those freedoms?

First, Freedom Zero is the freedom to run the program for any purpose, any way you like. Freedom One is the freedom to help yourself by changing the program to suit your needs.

Freedom Two is the freedom to help your neighbor by distributing copies of the program. And Freedom Three is the freedom to help build your community by publishing an improved version so others can get the benefit of your work.

Free Software DOES NOT mean the software is free as in free beer. Nothing forbids you to sell your software for 1000000 dollars or give it away for free if you wish. It does NOT mean "non-commercial".

It is defined as opposed to so-called proprietary/non-free softwares, that was particularly common back at the time (and still is today...). It has NOTHING to do with closed-source as opposed to open-source softwares.

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) was created to promote the ideology of Free Software and to promote making Free Software.

You can read on Business Insider a recent example of misrepresentation of the Free Software ideology (Free confused with free beer as opposed to Freedom + Stallman wrongly related to open-source): "He [Stallman] pioneered the concept of free and open source software (FOSS), whereby any programmer can create, contribute to, and give away software for free — offering viable alternatives to corporate-owned and created software."

There are hundreds of similar example of mischaracterization since the start of the movement.

The GNU Project and the Linux Kernel

In particular the FSF was raising funds from donations to hire developers to work on making a Free Operating System. It is the GNU Project.

An operating system (OS) is made on hell of a lot of different components, one of which being the kernel. Linus Torvalds had already created a kernel (a hardcore chunk of software) that was working well and that was also a Free Software: "Linux". Linux was used in the GNU OS and the GNU OS was finally released under the name "Linux" or "GNU/Linux". There is a controversy on the name of the OS: the FSF encourages people to use "GNU/Linux".

Copyright and software licensing

First of all, as creator of a software, you hold the full copyright over your work. You can distribute it under any license, and you're NOT legally entitled to follow the license you are choosing to distribute your software to, because you hold the copyright of the software. That's something many people are confused about.

You choose a license that says how OTHERS can use your software. Which rights and obligations you grant them when publishing your source code.

As creator of the initial project, by default you do not hold the copyright for the code the external contributors sent to your repository. As such, you may not have the right to do anything you want with their contributions. It depends on the license of their contribution. If the external contributors pushed their code to your repository on GitHub for instance, then the same license you chose will apply to their contribution.

However, there is a way to make external contributors hand-over their copyrights to you: the Contributor License Agreement (CLA). You can force them to sign this document before accepting their pull-request. There are many types of CLA, it is rather complex so I won't dive into it just yet.

GNU GPL

In order to enforce the 4 Freedoms of Free Software, Stallman created the GNU General Public License (GPL).

At its core, it does the following:

- you can do whatever you want when using the software for your own internal use.

- when distributing the software to somebody (as a commercial transaction or not), you must give them the source code. You cannot only give them binaries.

- then, the entity receiving the program is free to study the source code, modify it, sell it, redistribute it. They can even publish the source code online, but they don't have to and nobody can demand from them to get their modified version. They are free to keep it for them if they want. When redistributing the software, they must give the source code as well.

- anyone that make a modification to the GPL software keep his copyright to the portion of the code corresponding to his contribution

- if you make modification to the software in any way and use it for your internal use, you can do whatever you want.

- if you make modification to the software in any way and distribute it to somebody else, then your modified work must be licensed under the GNU GPL too and as such you must distribute the source code of the modified work to the person/entity you are distributing your modified software to.

The last point is the so-called "copyleft" effect. It means that by using a GNU GPL licensed software to make a modified work, you are somehow impeding your copyright over the modified work in the sense that you are obliged to use the same license GNU GPL when you distribute it. You will keep your copyright over your own work, but it is the result of the contract you accepted when you started using the GPL software to make your own.

The GNU GPL is sometimes refered by its detractors as "restrictive" and "viral" license. Developers tend not to understand why the Free Software guys talk about "freedom" all the while "restricting" the way newly created software is being used. That's because it is about freedom of the users. It is about freeing the software from one particular vendor, as is the case for proprietary softwares. It is also about freeing the software from the developers and transferring this freedom to the users. Not only freeing it from the initial developers but also all the subsequent ones - that is the very reason why copyleft has been created: to make sure any modifications of the software remain free. So that the source code can get its own life.

All the softwares released by the GNU Project are licensed under the GPL. Linux is also licensed under the GPL.

As you can see, by definition, GPL softwares are incompatible with proprietary softwares ;).

You may wonder how the heck can you make sure that nobody breaches this license, since the code lives its own life out there in the wild. Well, this is a real issue. The FSF gives legal support to anyone witnessing a GNU GPL infrigement. Sadly, many companies seem to embrace GPL violations, as with this 3D Printer or many Android-based OS.

Open-Source

Open-Source is a very different notion. It appeared later.

Linux, the kernel of the operating system GNU/Linux, was using the GNU GPLv2 as well. It was also a Free Software (which is why the GNU Project team accepted to use it as a replacement of their own kernel under development). However, its founder, Linus Torvalds, was not part of the GNU Project nor the FSF by itself.

The MIT and UC Berkeley were also working on softwares used in the first entirely open-source operating systems, the (GNU/)Linux OS. Why open-source? Because X Window, developed by the MIT is under X11 License (~= MIT License) and the networking softwares developed by UC Berkeley is under BSD License which are permissive licenses (see later for a definition). They were not part of the Free Software movement. Otherwise, they would have used the GNU GPL ;).

People working on GPL softwares were not necessarily always aligned with the ideology of the Free Software Foundation and Richard Stallman. When asked by Wonderview Productions in 2001 "What is Linux relationships with the GNU project?", part of Linus answer was "Well, there is relationships to GNU on kind of multiple levels, one is just the philosophical level of thinking that making your source open is a good idea. [...] You can think as Richard Stallman as the great philosopher. You can think of me as the engineer.". He refers to the FSF philosophy simply as "having the source open" rather than for the Freedom of users.

More recently, Linus opposed to the adoption of the latest version of the GNU GPL (version 3) partly due to the disagreement with Stallman's view on tivoization, a modern way to restrict the change of a copyleft software by locking it in the hardware itself. It is most likely used extensively by all portable devices: that's the reason why VLC remains at LGPLv2.

GPL does not enforce sharing per se, but the fact that anyone receiving a GPL licensed software can release the source code to the public makes it practically impossible for anyone to keep his work secret and make money out of it. That argument was valid only for non-internet based softwares but we will come to that later (GPL loop hole kinda closed by AGPL). As NDA over GPL work is illegal. Even though the person receiving the GPL software may not want to distribute it to the world, it became common that anyone making improvements to a GPL project was contributing it back to the community, especially with the rise of Version Control System online like GitHub, which made it incredibly easier to do so. Instead of having to distribute the source each time to each customer, you can put the source online with only a link.

People started realizing that Free Software enables online community to gather, to work from all over the world and to create incredible projects. With the Linux community, led by Linus Torvalds who thought "making the source open is a good idea," Open-Source movement was born. The term was created by Eric Raymond. Read "The Cathedral and the Bazar" for more info.

Open-Source is more about the technical side of the Free Software movement as opposed to the ethical and philosophical stance that the FSF insists on. It is really about the convenience of working together on a commonly shared source code. The license used is solely a tool for either enforcing the sharing of improvements or enabling more users to use the source code (permissive non-copyleft licenses - see later). It becomes a business model strategy.

Open-Source movement does not see any harm in combining proprietary and "open-source" softwares, since Open-Source is only a tool to achieve a better product, leveraging free (as in free beer) labour from all over the world. Open Source contributors are often passion-driven, especially back in the days. Open-Source is also a marketing tool used by businesses today to promote their softwares, penetrate more markets and encourage clients to use their products so that they can sell advanced "enterprise" features later. They may or may not use GPL to achieve such purpose. Since then, the use of GPL for a particular package was no longer enough to differentiate a project from the Free Softwares movement. The GPL can be used solely as a tool for business purposes (like with dual licensing - more about that later), to restrict the usage of a key library, or to enforce improvements.

FLOSS is Free(Libre) Open-Source Software and it refers to both Open-Source and Free Software indistinctively.

Source-available

A software is called "Open-Source" only if its source code is distributed to the public under a license validated by the Open Source Initiative. There are many criterias for a license to be accepted as an "Open-Source" license.

A software whose source code is distributed to the public under a license that is NOT validated by the Open Source Initiative is called "source-available software".

An open-source software is automatically source-available but a source-available software is not necessarily open-source.

Permissive vs Copyleft open-source licenses

There are many kind of Open-Source software licenses. We can classify them into copyleft and permissive licenses.

Copyleft licenses

Copyleft is often understood as follows:

- the modified work of the copyleft-licensed software has to abide by the same license

- when distributing the copyleft-licensed software, the source code of this software must be distributed too

Strong copyleft licenses

- The GNU GPL is a strong copyleft license because ANY modified work must also be distributed under the GNU GPL.

- The Affero General Public License (AGPL) is the same as GPL except that the event that defines "distribution" is extended to "making your software available to a user through a Network". It was designed for the modern internet era, when most softwares run on private servers and are never distributed physically to a user, all the while powering websites used by billions of people.

I have witnessed sooo many people on the web getting afraid of barely using an AGPL software on their computer. Such a paradox!!! There is a huge misunderstanding on AGPL. The point is: if you don't modify the code, you only have to make the software that's AGPL available to your users. But if you are the user of an AGPL software (like Signal or Bitwarden), then you have nothing to do. In fact, that's a plus for you as a user. You're using a software over which you have total control. You can see the code and you'll be sure that the source code of any improvement of this software will always be available to you.

It may be the consequence of several articles bashing AGPL, after Google decided to ban AGPL.

Weak copyleft licenses

The two most popular "weak" copyleft licenses are the Lesser General Public License (LGPL) and the Mozilla Public License (MPL). Their underlying philosophy are totally opposed:

- the LGPL was made by the FSF as a compromise to make more people use GPL-licensed softwares (i.e make proprietary vendors use Free Softwares). The copyleft effect is not systematically triggered to all kind of modified work.

- the MPL is a file-level copyleft license created by Mozilla to enable proprietary add-on (in particularly made by Mozilla) while encouraging some kind of improvements. It's more of an Open-Source philosophy type of license.

The LGPL is more complicated than the MPL and tends to be less used these days (the trend is simpler, more permissive licenses that are easy to embed into proprietary softwares - the open-source philosophy). However, the LGPL is more suitable for people who embrace the spirit of the Free Software movement.

More on the difference on my answer to this StackExchange question.

Permissive licenses

Among them, the most famous ones are:

They all share one thing in common. They all say: "use me however you want, even by combining me with other softwares, no matter Free Software or Proprietary Software, as long as you give attribution".

The most praised one these days is the Apache License for its protection against software patents. There is a huge debate over the very existence of software patents. In fact, many organizations have fought against it, like the FSF, the GNU Project and the Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure (FFII) which Pieter Hintjens led for two years. Read Pieter Hintjens for an opinionated essay against software patents. Listen to Richard Stallman 2 hours long talk about the dangers of software patents.

So if you have to choose one permissive license, go for Apache v2 ;).

License compatibility

All Free licenses are completely or partially incompatible with proprietary softwares (because of the copyleft effect). But not all OSS licenses are compatible with each other.

For example Apache v2 License is infamously incompatible with GNU GPLv2. This can be very annoying when you are working with some Kernel libraries released under (L)GPLv2. If you're anti-copyleft, then you have no choice but to use MIT or BSD (or equivalent) and you cannot have the patent protection offered by Apache v2.

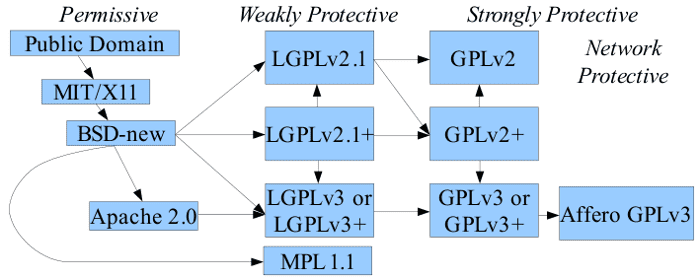

The following image summarizes the license compatibilities. It was extracted from Wikipedia, credits to David A. Wheeler.

That being said, all the latest versions of the modern most-used OSS licenses are compatible with each other. The real (voluntary) "issue" is the incompatibility of copyleft licenses with proprietary softwares.

Conclusion

Hopefully this article taught you a few things. Remember that choosing a license for a non-trivial software shall never be done lightly. It affects all aspects of your project: its philosophical/ethical stance, its attractivity to contributors/users and its business viability.

Previous article: